Common Culture – Paul Willis

From Common Culture: Symbolic work at play in the everyday cultures of the young by Paul Willis:

“In general the arts establishment connives to keep alive the myth of the special, creative individual artist holding out against passive mass consumerism, so helping to maintain a self-interested view of elite creativity…Against this we insist that there is a vibrant symbolic life and symbolic creativity in everyday life, everyday activity and expression – even if it is sometimes invisible, looked down on or spurned.”

“There can be a final unwillingness and limit even in subversive or alternative movements towards an arts democracy. They may have escaped the physical institutions and academies, but not always their conventions…we don’t want to start where ‘art’ thinks is ‘here’, from within its perspectives, definitions and institutions.[emphasis mine]”

“We argue for symbolic creativity as an integral (‘ordinary’) part of the human condition, not as inanimate peaks (popular or remote) rising above its mists.”

“Art is taken as the only field of qualitative symbolic activity…We insist, against this, that imagination is not extra to daily life, something to be supplied from disembodied art.”

“…young people feel more themselves in leisure than they do at work. Though only ‘fun’ and apparently inconsequential, it’s actually where their creative symbolic abilities are most at play. ”

“The fact that many texts may be classified as intrinsically banal, contrived and formalistic must be put against the possibility that their living reception [emphasis mine]is the opposite of these things.”

“Why shouldn’t bedroom decoration and personal styles, combinations of others’ ‘productions’, be viewed along with creative writing or song and music composition as fields of aesthetic realization?”

“Ordinary people have not needed an avant-gardism to remind them of rupture. What they have needed but never received is better and freer materials for building security and coherence in their lives.”

“The simple truth is that it must now be recognized that the coming together of coherence and identity in common culture occurs in surprising, blasphemous and alienated ways seen from old-fashioned Marxist rectitudes – in leisure not work [emphasis mine], through commodities not political parties, privately not collectively.”

What is so refreshing about this book is that it is filled with the actual accounts of lived responses to culture rather than the usual empty academic pronouncements about how culture is processed and taken up. Rather than opine, Willis listens.

Tiger Woods – Love – Agnès Poirier

“Without risk there can be no passion. Philosophers know that, beyond golf, romance is under threat”

“If this saga proves one thing, it is not Woods’s “malice”, but that love is threatened by the world’s two leading ideologies: libertarianism and liberalism. These two 21st-century diseases concur to make us believe that love is a risk not worth taking: as if we could have, on one hand, a safe conjugality; and on the other, sexual arrangements that will spare us the dangers of passion. Both are illusions.” from an article by Agnès Poirier here.

Risk, passion, love – something I wrote about at LeisureArts re: social practice in this post: Social Practice – Revelry and Risk – Art/Life

Art Work – Leisure

UPDATE: More here.

These comments pertain to the recent release of Art Work by Temporary Services. They apply to the project as a whole, but a link to them was left on Julia Bryan-Wilson’s essay “Art Versus Work” as it is a central organizing essay. I apologize in advance for the scatter-shot nature of the response. I level these criticisms and objections with great admiration of, and humility toward, Art Work, its organizers, and its contributors even if I don’t always maintain that tone.

Anything but work: Call Me a Slacker – NEVER a Worker.

“My father taught me to work; he did not teach me to love it. I never did like to work, and I don’t deny it. I’d rather read, tell stories, crack jokes, talk, laugh – anything but work.” – Abraham Lincoln

Julia Bryan-Wilson does an admirable job presenting a historical overview and theoretical foundation for those who embrace the notion of the artist as worker. What leaves me a bit cold, not just in her piece, but in Art Work as a whole, is the lack of any substantive dissent from this notion. At the very least, a sketch of some counter-theorizations, and a survey of key figures advocating against the valorization of work and labor would be useful. The slackers, quitters, idlers, loafers, drop outs, and leisure theorists have their own history, many providing a scathing critique of the lefts embrace of the proletarianization of human activity. I, being one of these good for nothings myself, hope to provide just such a sketch, but it will remain just a sketch as anything more would feel too much like work, and I’d rather read, tell stories, crack jokes, talk, laugh…

On work, labor, and old man Marx

“I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused

by the belief that work is virtuous…” – Bertrand Russell

Julia Bryan-Wilson writes, “Drawing on Marx’s theoretical work, and prompted by a desire to make art legitimate, necessary, and meaningful, artists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries tried to erode the distinction between art and labor by insisting that their actions, and the products of those actions, were indeed work.” The idea that calling what you do “work” makes it “legitimate” or “meaningful” is the crux of the problem I have with much of what one finds in Art Work. This sort of thinking is everywhere on the left and Marx does in fact provide the theoretical mirror in which many self-identified “cultural workers” (I always shudder at this phrase) see themselves. Jean Baudrillard, the still mostly Marxist incarnation of which Bryan-Wilson cites, moved very quickly into a position not easily integrated within her piece or this newspaper as a whole. In his book The Mirror of Production he writes “The critical theory of the mode of production does not touch the principle of production.” That is to say that Marxist analysis too readily embraces the terms of the debate and therefore provides a mere functional critique, one that Baudrillard might note, “…deciphers the functioning of the system of political economy; but at the same time it reproduces it as model.”

Like Baudrillard I see a certain kind of of Marxist theoretical fundamentalism at work here. Art, like everything else in life apparently, becomes just another form of work. The proponents of artist unions and art workers appear to see labor and production everywhere and thus we find ourselves talking of wages, compensation, and professional practices. Let’s keep in mind though that just as the id, ego, and superego are organizing myths of psychoanalysis, Marxism has its own myths. Mapping the world using these specialized tools is certainly useful in certain contexts, but I’d just like to keep in mind that they are specialized, very partial, and historically bound views and that they are maps after all. Or to return to Baudrillard in reference to Marxism:

“Historical materialism, dialectics, modes of production, labor power – through these concepts Marxist theory has sought to shatter the abstract universality of the concepts of bourgeois thought…Yet Marxism in turn universalizes them with a ‘critical’ imperialism as ferocious as the other’s.”

“…Thus, to be logical the concept of history must itself be regarded as historical, turn back on itself…Instead, in Marxism history is transhistoricized: it redoubles on itself and is universalized.”

“As soon as they [critical concepts] are constituted as universal they cease to be analytical and the religion of meaning begins [or what we called theoretical fundamentalism].”

Giles Gunn, not writing specifically about Marxism puts it this way, “Theory of this sort is always in danger of reifying itself – or, what amounts to the same thing, of treating everything it touches as mere epiphenomena of its own idioms. [emphasis mine]” So where does that leave us? What does employing these terms do? It seems many contributors here find them liberating. I feel it gives too much ground, too readily cedes a particular view of what is important about what artists do. I’m not sure that Baudrillard doesn’t have this one right:

“Failing to conceive of a mode of social wealth other than that founded on labor and production, Marxism no longer furnishes in the long run a real alternative to capitalism.”

And:

“And in this Marxism assists in the cunning of capital. It convinces men [sic] that they are alienated by the sale of their labor power, thus censoring the much more radical hypothesis that they might be alienated as labor power, as the ‘inalienable’ power of creating value by their labor. [entire quote in italics in the original]”

I see in Bryan-Wilson’s apparent acceptance of Marx a failure of imagination of sorts, one that leads us reductively to seeing the world through a narrow, economic prism. Much like the psychoanalyst sees libidinal drives and frustrated sexuality in everything from their morning coffee to flower arrangements, many in Art Work, see money, labor, and production everywhere. This strikes me as unhealthy and teeters dangerously close to the history of conceptual imperialism employed by Western ethnographers when they interpreted other cultures through their own cultural matrix and mistook this reading as transcription rather than translation. Baudrillard, again in The Mirror of Production is helpful here:

“…it [Western culture] reflected on itself in the universal, and thus all other cultures were entered in its museum as vestiges of its own image. It ‘estheticized’ them, reinterpreted them on its own model, and thus precluded the radical interrogation these ‘different’ cultures implied for it.”

Continuing:

“In the kindest yet most radical way the world has ever seen, they have placed these objects [so called primitive art] in a museum by implanting them in an esthetic category. But these objects are not art at all. And, precisely their non-esthetic character could at last have been the starting point for a radical perspective on (and not an internal critical perspective leading to a broadened reproduction of) Western culture.”

If we substitute “esthetic” with “economic” it should become clear why this is pertinent. By seeing something that looks like what the West calls economic exchange or labor and calling it such, we miss the opportunity to observe something deeply challenging to the very premise of economy, value, and work. To extrapolate then, we should think long and hard about how readily we want to place art within the conceptual spreadsheet of capitalist vocabulary, or as Baudrillard would say, its mirror – Marxist vocabulary.

Art work or Art leisure?

“…with art-relaxing art comes to you with a greater simplicity clearness beauty reality feelingness and life.” – Gilbert and George

“…there is no art without laziness.” – Mladen Stilinovic

Leisure, Joseph Pieper, the “intellectual worker,” and de-proletarianization

“Leisure has had a bad press. For the puritan it is the source of vice; for the egalitarian a sign of privilege. The Marxist regards leisure as the unjust surplus, enjoyed by the few at the expense of the many.” – Roger Scruton

“Work does not make you rich; it only makes you bent over.” – Russian proverb

One doesn’t have to look very far to find alternatives to the worship of work. Josef Pieper’s book Leisure, The Basis of Culture provides a road map to rethinking many of the founding assumptions of Art Work. Tackling head on what he calls the culture of “total work,” Pieper argues for leisure as an organizing principle for culture. He is especially scornful of the notion of the “intellectual worker” from which the easy leap to “art worker” should be obvious. He writes, “…the takeover…of intellectual action…and its exclusive possession by the realm of ‘total work’…the most recent phase of a whole series of conquests made by the ‘imperial figure’ of the ‘Worker.’ And the concepts of intellectual worker and intellectual work…make the fact of that conquest especially clear and especially challenging to our times.”

He goes on to provide a historical summary of how the idea of effort, work, and labor came to be equated with knowing and how this transformation omitted the very basis of intellectus, the passive, listening, visionary, effortless dimension of knowing at the expense of ratio, the mostly discursive, active form. As he describes it, many in this publication seem to have followed this same path of over-valuing effort and difficulty. So in Art Work it becomes clear that “…not only the wage earner, the hand-worker, and the proletarian are workers; even the learned man, the student, are workers; they too are drawn into the social system and its distribution of labor. the intellectual worker…is a functionary in the total world of work, he may be called a ‘specialist,’ he is still a functionary…nobody is granted a ‘free zone’ of intellectual activity…” In this I sense a sad resignation to proletarianization, but what if we sought rather de-proletarianization?

Pieper defines being proletarian as “being bound to the working-process.” This he argues leads one to become a “spiritually impoverished functionary” – and it is this that rings loudly when I see one embrace the term art worker. For once again it seems like a failure of imagination, a spiritual failure (knowing full well how unfashionable that must seem) to adopt, if even tactically, the rhetoric of total work, or “to fall into line as ready functionaries for the collective working-state.” What is the alternative? Rather than expanding the reach of work, its colonization of existence, its imperial nature, perhaps it is better to tame it, refuse it (to the extent one can), and most easily, reject its measures. As Pieper says de-proletarianization “would consist in making available for the working person a meaningful kind of activity that is not work – in other words, by opening up an area of true leisure.”

Slack

Another prism through which to read all of this is through the “paradoxes of slackerdom” – an online conference I co-organized with Stephen Wright here. In its own way that (international) conversation stands as a kind of rejoinder to this one, or at least a necessary supplement. I urge those who have found their way here to look not only at it, but at the legions of lazy sods, slackers, and others that reject work altogether as the (only) measure of human worthiness – those that seek to define their lives relative to, and in, leisure – what Paul Willis calls “the hidden continent of the informal.”

Robert Skidelsky – The Good Life – Wealth

“In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that in 100 years – that is, by 2030 – growth in the developed world would, in effect, have stopped, because people would “have enough” to lead the “good life.” Instead, the accumulation of wealth, which should be a means to the “good life,” has become an end in itself because it destroys many of the things that make life worth living.” – Robert Skidelsky in an article here. I would offer a minor corrective to Skidelsky and qualify his use of wealth as material/monetary wealth which tends to destroy other forms of wealth the *other* things that make life worth living (via Jerome Segal) – transcendent meaning, aesthetic experience, social/loving relationships/neighborliness, intellectual growth…

David McCandless – The Visual Miscellaneum – Randall Szott

My project “is the new” has had many lives. It first appeared here. Later, it was reworked here. That, in turn led to its appearance in the Boston Globe here. It sat dormant for a while but has been reworked yet again, this time by David McCandless and it now appears as “X is the new black” in his book The Visual Miscellaneum.

Alexander Koch – Quitting – Stephen Wright

“Why would an ex-artist potentially bring more creativity, more imagination or more self-responsibility to natural sciences and medicine than anybody else. I think Richard Rorty (whom we both admire) would actually support me here. If artists merely become social scientists or long-distance runners, or if they do become social scientists or long-distance runners “as artists”, would sound for him a) as really hard to distinguish, b) unclear what this distinction is good for, and c) sound like an attempt to find something essential about what artists are, exactly in the very moment of their disappearance, whereas my theoretic proposals of the artistic dropout try to contribute to an anti-essentialist perspective on that disappearance.” – from an amazing interview here.

Leisure – Jerome Segal – Graceful Simplicity

Thinking more deeply about the politics of leisure. Jerome Segal calls it “graceful simplicity,” but we basically mean the same thing. He states, “A politics of simplicity seeks a world that is not hectic, not filled with anxiety. It is a world in which people have sufficient time to do things slowly and to do them right, whether what they are doing is building and enjoying a friendship, working on sculpture, or studying scripture.”

Carrol Dunham – He Said She Said – Review

Our show at He Said – She Said featuring Carroll Dunham received this review.

Our show at He Said – She Said featuring Carroll Dunham received this review.

InCUBATE – In Search of the Mundane – threewalls

I had the good fortune of working with my friends InCUBATE and threewalls for an event series called In Search of the Mundane. You can see more here and read a (sort of) review here.

I had the good fortune of working with my friends InCUBATE and threewalls for an event series called In Search of the Mundane. You can see more here and read a (sort of) review here.

David Robbins – An Imaginative Elsewhere

“All the time, though, my sensibility pointed toward and yearned for an imaginative Elsewhere. I became increasingly dissatisfied with the narrowness of art as a formulation of the imagination. This will sound preposterous to many people, I’m aware, given that art offers and represents extraordinary behavioral freedoms, but in “making art” I found an ultimately enslaving formulation. How so? In art, you can do, yes, anything you want so long as you’re willing to have it end up as art. That isn’t real imaginative freedom, in my view. Inquisitiveness of mind will carry you past art, and apparently I love inquisitiveness of mind more than I love art.” – David Robbins [emphasis mine]

Love – Education – R.R. Reno

“Loyal to our critical principles, we can barely squeak out the slenderest of affirmations. Fearful of living in dreams and falling under the sway of ideologies, we have committed ourselves to disenchantment…What we need, therefore, is to rethink our educational self-image and subordinate the critical moment to a pedagogy that encourages the risks of love’s desire.” – R.R. Reno

MOMA – Gourd Museum

“I would much rather be in the Charles and Mary Johnson Gourd Museum in Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina. I’d rather be there because I have no familiar categories to make sense of it. I’d rather be there because it unnerves me, and reminds me that there are things in life too strange for knee jerk irony. I’d rather be there because it will never have a mass market or become a ministry of culture.” – Immanent Domain via Suggested Donation

Sunday Soup Houston – InCUBATE – SKYDIVE – Saturday Free School for the Arts

Saturday, April 4th 2009

I’m doing a talk with InCUBATE at the Saturday Free School for the Arts in Houston, TX.

“Saturday Free School for the Arts will offer a range of skill shares, lectures, and workshops. It is a fluid structure where teachers become students and pupils can become teachers. Members of the community will be invited to teach and may also propose seminars. In the tradition of free schools, the Saturday Free School is an ever shifting and open collective of artists and participants, who gather together at the Skydive, a contemporary arts space in Houston. Saturday Free School for the Arts remains responsive to the interests of its participants. Through a community of artists Saturday Free School offers freedom from expensive and immutable educational institutions. Saturday Free School for the Arts provides workshops, classes and skill-shares at no cost to it’s participants.”

Sunday, April 5th 2009

Sunday Soup at SKYDIVE. Nancy Zastudil and I are bringing InCUBATE to Houston for Sunday Soup Texas style.

“SKYDIVE utilizes an open and collaborative model for producing its programming. A group of artists, curators, and other professionals function as Advisors to help create shows, invite artists, and collaborate in the mission and programming of the space. Participants in SKYDIVE will be invited to Houston for a sustained number of days, previous to the exhibition to make their work, interact with the Houston community and see the sites in Houston and surrounding areas.”

Qualities of Thinking – Scholarly Virtues

“At present research focuses on the scholarly virtues: accuracy of reference and care in drawing conclusions. These are valuable because they counteract our normal sloppy thinking. However, there are many more qualities of thinking: grace, charisma, intimacy, spontaneity, wit, depth, simplicity, grandeur, warmth, openness, drama, intensity and generosity. [emphasis mine] These vital and passionate qualities are linked to the power of ideas, the ways in which ideas get inside our lives and come to matter in everyday existence.” – John Armstrong as quoted here.

Michael Stickrod – He Said She Said – Review

Our current show at He Said – She Said featuring Michael Stickrod received this nice review.

Altermodern – Nicolas Bourriaud – Pity the curatorial studies student

“The whole mélange is served up with the thick buttery sauce of French art theory, and the catalogue essays will give anyone except a curatorial studies MA student a crise de foie.” – Ben Lewis on Bourriaud’s Altermodern at The Tate

An update. Stewart Home has a way with words:

“The art itself doesn’t really matter, it is there to illustrate a thesis. The thesis doesn’t matter either since it exists to facilitate Bourriaud’s career; and Bourriaud certainly doesn’t matter because he is simply yet another dim-witted cultural bureaucrat thrown up by the institution of art.”

More here: Bourriaud’s ‘Altermodern’, an eclectic mix of bullshit & bad taste

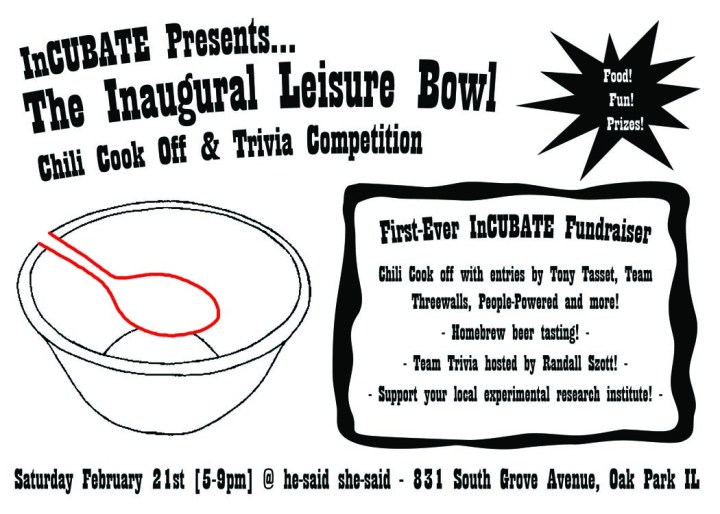

He said & InCUBATE present: The Inaugural Leisure Bowl

The latest event from He said – She said & InCUBATE.

Carl Wilson – Love – Criticism

Some quotes on criticism from Let’s Talk About Love by Carl Wilson:

“A few people have asked me, isn’t life too short to waste time on art you dislike? But lately I feel like life is too short not to.”

“I cringe when I think about what a subcultural snob I was five or ten years ago, and worse in my teens and twenties, how vigilant I was against being taken in – unaware that I was also refusing an invitation out. In retrospect, this experiment seems like a last effort to purge that insularity, so that the next phase might happen in a larger world, one beyond the horizon of my habits. For me, adulthood is turning out to be about becoming democratic.”

“The kind of contempt that’s mobilized by ‘cool’ taste is inimical…to an aesthetics that might support a good public life.”

“I would be relieved to have fewer debates over who is right or wrong about music, and more that go, “Wow, you hate all the music I like and I hate all the music you like. What might we make of that?”

What would criticism be like if it were not foremost trying to persuade people to find the same things great…It might…offer something more like a tour of an aesthetic experience, a travelogue, a memoir.”

“…a more pluralistic criticism might put less stock in defending its choices and more in depicting its enjoyment, with all the messiness and private soul tremors – to show what it is like for me to like it, and invite you to compare.”

Child Development – Marc Briod – Phenomenology

“[children develop] in an open, creative venture of living toward the future…Moreover, it would be described as a life of creative openness, not self-made, but creative in the exact degree to which it is open to the newness and freshness of experience, and to its own life as a continual return to the sedimented layers of existing, intentionalities, meanings and projects.” – Marc Briod, “A Phenomenological Approach to Child Development”

Kaprow – Unart

“This is not because I don’t like the arts, or that I’m not interested in the arts of other people. But as far as I was personally concerned, the un-arting process was primary and, therefore, I would not find useful any integration of social and cultural theory into art-making.” – Allan Kaprow

Slacker – Leisure – n.e.w.s – Stephen Wright

FYI:

An online slacker summit will take place from 1/2-1/6 at n.e.w.s.

Cutting Slack

By both slacking off from the imperative to work and, symmetrically, deliberately abstaining from leisure, slackers embody a fascinating – and for the productivist majority, infuriating – performative paradox. Slackers don’t “just” slack off; they go at it full-tilt. Performing laziness – that is, the studied and ostentatious practice of doing not much – is all-consuming. But is it subversive? Does it have seditious potential within a regime of productivism? Can it be decreative, obstructing the reifying thrust of the “creative” industry and class with their “artistic research projects”? To answer these questions in the affirmative is to imagine that slackers might come to constitute something of a political community, however slack. But, as Randall Szott has asked, are communities formed by slack not also bound by slack, that is, to entropic collapse without even really working at it? Or can they, martial arts-style, lackadasically harness the surplus force of the productivist adversary? Over the course of this weekend forum, we will ride the slack tide to consider these questions. In suitably slack fashion.

The moderator will be Stephen Wright.

I’ll be the “special guest.”

Confirmed participants include:

Brian Holmes – Continental Drift

Chris Carlsson – Nowtopia and Processed World

Andy Abbott – Festival of Pastimes and http://www.andyabbott.co.uk/

Katherine Carl – NAO

Sal Randolph – http://salrandolph.com/

Hideous Beast – http://www.hideousbeast.com/

Many more T.B.A

Please contact me if you’d like more info on how to join the conversation!

Robert C. Solomon – The Art of Living – Professionalization of Philosophy/Art

“Philosophy is essentially an art. It is the art of living, the search for wisdom.”

“What gives our lives meaning is not anything beyond our lives, but the richness of our lives.”

– Robert Solomon

I’ve written before about Robert Solomon at LeisureArts:

Robert C. Solomon – Passionate Life – Raoul Vaneigem

Philosophy – LeisureArts – Passion

I recently read his The Passions: Emotions and The Meaning of Life. In it, Solomon argues that “…emotions are the meaning of life. It is because we are moved, because we feel, that life has meaning. The passionate life, not the dispassionate life of pure reason, is the meaningful life.” The central thesis of his book is of great interest, but I unfortunately found his deep commitment to existentialist responsibility off putting. Despite that, the core argument is a necessary salvo at the analytic/rationalist mafia.

What is of real interest to me is his introductory riff on the professionalization of philosophy and its impact on our lives.

“Let me be outrageous and insist that philosophy matters. It is not a self-contained system of problems and puzzles, a self-generating profession of conjectures and refutations…We are all philosophers; the problems we share are philosophical problems. What has been sanctified and canonized as ‘philosophy’ is but the cream of curdled thought from the minds of men [sic] rare in genius, but common in their concerns.”

Solomon, throughout many of his works revisits the theme of what he calls (professional) philosophy’s “thinness.” He maintains that the aforementioned puzzles ultimately devolve into examining narrower and narrower slices of human experience. In its attempt to emulate the precision and appearance of objectivity of the sciences, philosophy has developed into highly “sophisticated irrelevancy.”

In his defense of the passions he posits that their subjective nature is a strength, not a weakness. The passions add to, rather than inhibit our understanding of reality. Of course it is not the capital R reality of professional philosophy that he thinks should be the ultimate aim of philosophical inquiry. “They [the passions] are not concerned with the world, but my world. They are not concerned with ‘what is really the case’ with ‘the facts,’ but rather with what is important.”

It is professional philosophy with its system of rewards for esoteric argumentation and refutation that all too often dispenses with what is important to the everyday concerns of people outside the discipline. Or as Solomon puts it:

“Nothing has been more harmful to philosophy than its ‘professionalization,’ which on the one hand has increased the abilities and techniques of its practitioners immensely, but on the other has rendered it an increasingly impersonal and technical discipline, cut off from and forbidding to everyone else.”

He calls this “tragic” and yearns for philosophy’s return to the streets where “Socrates originally practiced it.” The parallels with the professionalization of art should be obvious enough. In fact, Solomon has called philosophy “conceptual sculpture,” but his usage refers to the shaping of the mental structures that shape our everyday lives. There’s too much at stake in both these fields to leave them to the academic class. They must not be about life, but serve it.

Bruce Fleming – Professionalization of Literature

From Bruce Fleming’s “What Ails Literary Studies”:

“We’re not teaching literature, we’re teaching the professional study of literature: What we do is its own subject. Nowadays the academic study of literature has almost nothing to do with the living, breathing world outside. The further along you go in the degree ladder, and the more rarified a college you attend, the less literary studies relates to the world of the reader. The academic study of literature nowadays isn’t, by and large, about how literature can help students come to terms with love, and life, and death, and mistakes, and victories, and pettiness, and nobility of spirit, and the million other things that make us human and fill our lives. It’s, well, academic…That’s how we made a discipline, after all.”

There are some conservative overtones to his piece, but he’s right on the mark with regard to the way professionalization can stifle human experience. I found myself substituting ‘art’ for ‘literary studies,’ but pretty much any disciplinary field is applicable.

2 comments