Creating art by doing nothing – Félicien Marboeuf and rejecting the productivist approach to culture – “My art is that of living”

“Can artists create art by doing nothing?” – Andrew Gallix

More than 20 artists will pay homage to Félicien Marboeuf in an eclectic exhibition opening in Paris next week. Although he’s hardly a household name, Marboeuf (1852-1924) inspired both Gustave Flaubert and Marcel Proust. Having been the model for Frédéric Moreau (Sentimental Education), he resolved to become an author lest he should remain a character all his life. But he went on to write virtually nothing: his correspondence with Proust is all that was ever published – and posthumously at that. Marboeuf, you see, had such a lofty conception of literature that any novels he may have perpetrated would have been pale reflections of an unattainable ideal. In the event, every single page he failed to write achieved perfection, and he became known as the “greatest writer never to have written”. Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter, wrote John Keats.

…The artists he brings together all reject the productivist approach to art, and do not feel compelled to churn out works simply to reaffirm their status as creators. They prefer life to the dead hand of museums and libraries, and are generally more concerned with being (or not being) than doing. Life is their art as much as art is their life – perhaps even more so.

…

…Jouannais celebrates the skivers of the artistic world, those who can’t be arsed. “If I did anything less it would cease to be art,” Albert M Fine admitted cheekily on one occasion. Duchamp also prided himself on doing as little as possible: should a work of art start taking shape he would let it mature – sometimes for several decades – like a fine wine.

3:am cult hero: félicien marboeuf – Andrew Gallix

With his bovine-sounding surname, Félicien Marboeuf (1852-1924) seemed destined to cross paths with Flaubert. He was the inspiration for the character of Frédéric Moreau in L’Education sentimentale, which left him feeling like a figment of someone else’s imagination. In order to wrest control of his destiny, he resolved to become an author, but Marboeuf entertained such a lofty idea of literature that his works were to remain imaginary and thus a legend was born. Proust — who compared silent authors à la Marboeuf to dormant volcanoes — gushed that every single page he had chosen not to write was sheer perfection.

Or did he? One of the main reasons why Marboeuf never produced anything is that he never existed. Jean-Yves Jouannais planted this Borgesian prank at the heart of Artistes sans oeuvres when the book was first published in 1997. The character subsequently took on a life of his own, resurfacing as the subject of a recent group exhibition and, more famously, in Bartleby & Co., Enrique Vila-Matas’ exploration of the “literature of the No”. Here the Spanish author repays the debt he owes to Jouannais’s cult essay (which had been out of print until now) by prefacing this new edition.

Marboeuf has come to symbolize all the anonymous “Artists without works” past and present. Through him, Jouannais stigmatizes the careerists who churn out new material simply to reaffirm their status or inflate their egos, as well as the publishers who flood the market with the “little narrative trinkets” they pass off as literature on the three-for-two tables of bookshops. In so doing, he delineates a rival tradition rooted in the opposition to the commodification of the arts that accompanied industrialization. A prime example is provided by the fin-de-siècle dandies who reacted to this phenomenon by producing nothing but gestures. More significantly, Walter Pater’s contention that experience — not “the fruit of experience” — was an end in itself, led to a redefinition of art as the very experience of life. A desire to turn one’s existence into poetry — as exemplified by Arthur Cravan, Jacques Vaché or Neal Cassady — would lie at the heart of all the major twentieth-century avant-gardes. “My art is that of living”, Marcel Duchamp famously declared, “Each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral; it’s a sort of constant euphoria.”

of things too important to be left to “professionals” – Amateurs and culture

Amateurs: Wherein I am advised to ‘get some’ – Steven Poole

It may be ironic that a professor of “language studies” uses the term “amateur” as an insult, since he no doubt knows that for most of its life it meant someone who did something for love (Latin amo) rather than for money, and only acquired its dismissive sneer during the bureaucratic twentieth century. George Orwell, of course, was an “amateur” in the field of analysing political language, and even recommended that more of his regular work, book-reviewing, be done by “amateurs”:

Incidentally, it would be a good thing if more novel reviewing were done by amateurs. A man who is not a practised writer but has just read a book which has deeply impressed him is more likely to tell you what it is about than a competent but bored professional. That is why American reviews, for all their stupidity, are better than English ones; they are more amateurish, that is to say, more serious.

Of course, “amateurs” are not everywhere to be celebrated. I would not like to have root-canal surgery performed on me by an amateur dentist. Not everyone has a valid opinion on medicine. On the other hand, we are all language-users. Very many of the “amateurs” who have attended my talks on Unspeak think in careful and sophisticated ways about language, and their opinions are not to be dismissed simply because they haven’t had the right sort of academic training. My view, indeed, is that the analysis of language in politics is too important to be left to “professionals” who murmur among themselves in the diagrammatic glades of “discourse analysis” and other subdisciplines. Professor Salkie surely knows, to be blunt, that nowadays, “amateur” is most often the kneejerk insult of the salaryman who desires to protect his own turf.

“the nebula of “offroad conceptualists” who have withdrawn from the artworld attention economy into the shadows, never performing what they do as art.” – Stephen Wright on “art without qualities”

[Stephen Wright is one of the last truly vibrant theorists left in the art world. Although maybe that is because he spends so much time outside the art world. And maybe his early years in the Pacific Northwest gifted him with the temerity of a cryptozoologist (escapologist). He is relentlessly innovative with turns of phrase and new memes, not in some pointlessly entrepreneurial attention seeking way, but as a matter of necessity – because the things he is trying to describe are outside “accepted formal parameters of art” (as he quotes Raivo Puusemp saying in this post). Wright, if not a member himself of the “offroad conceptualists,” is surely their greatest chronicler.]

…Upon resigning as mayor, Puusemp left Rosendale forever, moving to somewhere in Utah, and thereby joining the nebula of “offroad conceptualists” who have withdrawn from the artworld attention economy into the shadows, never performing what they do as art.

Of course plenty of things are not performed as art (in many cases because they just aren’t) although their coefficient of art — in terms of their form, contextual engagement and the competence they epitomize — would be largely adequate for them to successfully lay claim to artistic status. And it is precisely this issue which makes Raivo Puusemp’s short preface to Beyond Art so compelling. From it can be deduced an entirely original and under-theorized line of institutional critique as the background of his project to instantiate a plausible new artworld in Rosendale, A public work.

But before considering the underpinnings of the project laid out in the document’s preface, let’s pause for a moment to consider just exactly what “not performing art” means in the case of Raivo Puusemp. Since his stint as mayor of Rosendale, Puusemp has ceased making art; he hasn’t even done art. But he’s thought it. Meaning that he’s not so much a former concept artist, as that he remains an artiste sans oeuvre. Not in the affected sense of a dandy, but with the infectious humility of concept art. As he put it in a recent public conversation with curator Krist Gruijthuijsen at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (one of the venues to recently host a retrospective of the artist’s work, up to and including his stint as mayor) Puusemp acknowledged as much, at least implicitly, describing how his relationship to art had itself become conceptual. “I’ve always thought about art, I just haven’t done it. I would see something, and think someone should do that. But I would never do it myself.”

…He’s sees conceptual-artistic potential in any number of situations, relations and things, contemplates making it art, but leaves the doing, the making, the “performing” (or not) to others.

Of course, this principled imperformativity only makes sense against Puusemp’s background as an active artist in the 1970s. This is the paradox of the imperformative: not-doing only has traction against a horizon of reasonable expectation of an ability-to-do and the deed itself. Countless things don’t get done, but the imperformative implies that something actually eludes performative capture — that it is done quietly, and not necessarily materially (who knows?) in the shadows. And the shadow of the deed is the idea. But the very fact that Puusemp would be inclined to contemplate people performing (or not) ideas he had thought of also stems directly from his previous artistic practice.

…

Several things happened that would lead Puusemp to choose to move into the shadows. For one thing, he became involved with an underground group in New York City called “Museum” which allowed him to understand art as an essentially collective endeavor and to gain insight into group dynamics and process. But above all, he writes, “it became apparent that art was a continuum of predictable steps each built upon the last. It seemed that by being familiar with the then accepted formal parameters of art, and by doing work within those parameters, there was a great likelihood of art community acceptance of that work. Creative leaps were reduced to inevitable innovations and predictable steps. I became fascinated with the process of conception to completion rather than the product. From that point, I found it difficult to continue making art within the standard context.”

…

–Did you still think of yourself as an artist?

–It’s hard to say. I just kind of walked away from it, or from the object stuff anyway. I was thinking about things a lot. I mean, the other thing is, I started looking at this Rosendale thing more and more as a piece of art. It was a strange thing to do, like living a dual life. On the one hand, I was doing this thing, but I couldn’t tell people I was doing it because they would think I was using them or kind of manipulating the whole thing.

–But was it always intentional for you that running for mayor would be an artwork?

–I think it evolved. I was intrigued by the possibility…Raivo Puusemp, a possibilitarian? That was the term (Möglichkeitsmensch) that Robert Musil coined to describe Ulrich, his Man Without Qualities. Not because his protagonist was without quality — his insights were of exceeding quality — but because he possessed none that determined the others and locked him down into a particular ontology. We tend to think of artworks as characterized by a deep singularity — and as the documents on Rosendale’s dissolution show, it was a project so steeped in nitty-gritty singularity as to conceal its self-understanding as art. But as a morphing pursuit of intriguing possibilities, and in light of Puusemp’s decision to further withdraw from exercising artistic agency, Rosendale, A Public Work may be seen as paving the way toward an art without qualities.

“School is a good place for learning to do just what someone else wants you to do; it’s a terrible place for practising creativity.” – The culture of “achievement” agreed upon by do-gooder liberal bureaucrats and conservative economic zealots

When I was a child in the 1950s, my friends and I had two educations. We had school (which was not the big deal it is today), and we also had what I call a hunter-gather education. We played in mixed-age neighbourhood groups almost every day after school, often until dark. We played all weekend and all summer long. We had time to explore in all sorts of ways, and also time to become bored and figure out how to overcome boredom, time to get into trouble and find our way out of it, time to daydream, time to immerse ourselves in hobbies, and time to read comics and whatever else we wanted to read rather than the books assigned to us. What I learnt in my hunter-gatherer education has been far more valuable to my adult life than what I learnt in school, and I think others in my age group would say the same if they took time to think about it.

…

The decline in opportunity to play has also been accompanied by a decline in empathy and a rise in narcissism, both of which have been assessed since the late 1970s with standard questionnaires given to normative samples of college students. Empathy refers to the ability and tendency to see from another person’s point of view and experience what that person experiences. Narcissism refers to inflated self-regard, coupled with a lack of concern for others and an inability to connect emotionally with others. A decline of empathy and a rise in narcissism are exactly what we would expect to see in children who have little opportunity to play socially. Children can’t learn these social skills and values in school, because school is an authoritarian, not a democratic setting. School fosters competition, not co-operation; and children there are not free to quit when others fail to respect their needs and wishes.

In my book, Free to Learn (2013), I document these changes, and argue that the rise in mental disorders among children is largely the result of the decline in children’s freedom. If we love our children and want them to thrive, we must allow them more time and opportunity to play, not less. Yet policymakers and powerful philanthropists are continuing to push us in the opposite direction — toward more schooling, more testing, more adult direction of children, and less opportunity for free play.

…

Learning versus playing. That dichotomy seems natural to people such as my radio host, my debate opponent, my President, my Education Secretary — and maybe you. Learning, according to that almost automatic view, is what children do in school and, maybe, in other adult-directed activities. Playing is, at best, a refreshing break from learning. From that view, summer vacation is just a long recess, perhaps longer than necessary. But here’s an alternative view, which should be obvious but apparently is not: playing is learning. At play, children learn the most important of life’s lessons, the ones that cannot be taught in school. To learn these lessons well, children need lots of play — lots and lots of it, without interference from adults.

…

Hunter-gatherers have nothing akin to school. Adults believe that children learn by observing, exploring, and playing, and so they afford them unlimited time to do that. In response to my survey question, ‘How much time did children in the culture you observed have for play?’, the anthropologists unanimously said that the children were free to play nearly all of their waking hours, from the age of about four (when they were deemed responsible enough to go off, away from adults, with an age-mixed group of children) into their mid- or even late-teenage years (when they would begin, on their own initiatives, to take on some adult responsibilities). For example, Karen Endicott, who studied the Batek hunter-gatherers of Malaysia, reported: ‘Children were free to play nearly all the time; no one expected children to do serious work until they were in their late teens.’

This is very much in line with Groos’s theory about play as practice. The boys played endlessly at tracking and hunting, and both boys and girls played at finding and digging up edible roots. They played at tree climbing, cooking, building huts, and building other artefacts crucial to their culture, such as dugout canoes. They played at arguing and debating, sometimes mimicking their elders or trying to see if they could reason things out better than the adults had the night before around the fire. They playfully danced the traditional dances of their culture and sang the traditional songs, but they also made up new ones. They made and played musical instruments similar to those that adults in their group made. Even little children played with dangerous things, such as knives and fire, and the adults let them do it, because ‘How else will they learn to use these things?’ They did all this, and more, not because any adult required or even encouraged them to, but because they wanted to. They did it because it was fun and because something deep inside them, the result of aeons of natural selection, urged them to play at culturally appropriate activities so they would become skilled and knowledgeable adults.

In another branch of my research I’ve studied how children learn at a radically alternative school, the Sudbury Valley School, not far from my home in Massachusetts. It’s called a school, but is as different from what we normally think of as ‘school’ as you can imagine. The students — who range in age from four to about 19 — are free all day to do whatever they want, as long as they don’t break any of the school rules. The rules have nothing to do with learning; they have to do with keeping peace and order.

To most people, this sounds crazy. How can they learn anything? Yet, the school has been in existence for 45 years now and has many hundreds of graduates, who are doing just fine in the real world, not because their school taught them anything, but because it allowed them to learn whatever they wanted. And, in line with Groos’s theory, what children in our culture want to learn when they are free turns out to be skills that are valued in our culture and that lead to good jobs and satisfying lives. When they play, these students learn to read, calculate, and use computers with the same playful passion with which hunter-gatherer kids learn to hunt and gather. They don’t necessarily think of themselves as learning. They think of themselves as just playing, or ‘doing things’, but in the process they are learning.

Even more important than specific skills are the attitudes that they learn. They learn to take responsibility for themselves and their community, and they learn that life is fun, even (maybe especially) when it involves doing things that are difficult. I should add that this is not an expensive school; it operates on less than half as much, per student, as the local state schools and far less than most private schools.

…

President Obama and his Education Secretary, Arne Duncan, along with other campaigners for more conventional schooling and more tests, want children to be better prepared for today’s and tomorrow’s world. But what preparation is needed? Do we need more people who are good at memorising answers to questions and feeding them back? Who dutifully do what they are told, no questions asked? Schools were designed to teach people to do those things, and they are pretty good at it. Or do we need more people who ask new questions and find new answers, think critically and creatively, innovate and take initiative, and know how to learn on the job, under their own steam? I bet Obama and Duncan would agree that all children need these skills today more than in the past. But schools are terrible at teaching these skills.

…

You can’t teach creativity; all you can do is let it blossom. Little children, before they start school, are naturally creative. Our greatest innovators, the ones we call geniuses, are those who somehow retain that childhood capacity, and build on it, right through adulthood. Albert Einstein, who apparently hated school, referred to his achievements in theoretical physics and mathematics as ‘combinatorial play’. A great deal of research has shown that people are most creative when infused by the spirit of play, when they see themselves as engaged in a task just for fun. As the psychologist Teresa Amabile, professor at Harvard Business School, has shown in her book Creativity in Context (1996) and in many experiments, the attempt to increase creativity by rewarding people for it or by putting them into contests to see who is most creative has the opposite effect. It’s hard to be creative when you are worried about other people’s judgments. In school, children’s activities are constantly being judged. School is a good place for learning to do just what someone else wants you to do; it’s a terrible place for practising creativity.

…

None of these people would have discovered their passions in a standard school, where extensive, free play does not occur. In a standard school, everyone has to do the same things as everyone else. Even those who do develop an interest in something taught in school learn to tame it because, when the bell rings, they have to move on to something else. The curriculum and timetable constrain them from pursuing any interest in a creative and personally meaningful way. Years ago, children had time outside of school to pursue interests, but today they are so busy with schoolwork and other adult-directed activities that they rarely have time and opportunity to discover and immerse themselves deeply in activities they truly enjoy.

To have a happy marriage, or good friends, or helpful work partners, we need to know how to get along with other people: perhaps the most essential skill all children must learn for a satisfying life. In hunter-gatherer bands, at Sudbury Valley School, and everywhere that children have regular access to other children, most play is social play. Social play is the academy for learning social skills.

The reason why play is such a powerful way to impart social skills is that it is voluntary. Players are always free to quit, and if they are unhappy they will quit. Every player knows that, and so the goal, for every player who wants to keep the game going, is to satisfy his or her own needs and desires while also satisfying those of the other players, so they don’t quit. Social play involves lots of negotiation and compromise. If bossy Betty tries to make all the rules and tell her playmates what to do without paying attention to their wishes, her playmates will quit and leave her alone, starting their own game elsewhere. That’s a powerful incentive for her to pay more attention to them next time. The playmates who quit might have learnt a lesson, too. If they want to play with Betty, who has some qualities they like, they will have to speak up more clearly next time, to make their desires plain, so she won’t try to run the show and ruin their fun. To have fun in social play you have to be assertive but not domineering; that’s true for all of social life.…

The golden rule of social play is not ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ Rather, it’s something much more difficult: ‘Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.’ To do that, you have to get into other people’s minds and see from their points of view. Children practise that all the time in social play. The equality of play is not the equality of sameness. Rather, it is the equality that comes from respecting individual differences and treating each person’s needs and wishes as equally important. That’s also, I think, the best interpretation of Thomas Jefferson’s line that all men are created equal. We’re not all equally strong, equally quick-witted, equally healthy; but we are all equally worthy of respect and of having our needs met.

…

In school, and in other settings where adults are in charge, they make decisions for children and solve children’s problems. In play, children make their own decisions and solve their own problems. In adult-directed settings, children are weak and vulnerable. In play, they are strong and powerful. The play world is the child’s practice world for being an adult. We think of play as childish, but to the child, play is the experience of being like an adult: being self-controlled and responsible. To the degree that we take away play, we deprive children of the ability to practise adulthood, and we create people who will go through life with a sense of dependence and victimisation, a sense that there is some authority out there who is supposed to tell them what to do and solve their problems. That is not a healthy way to live.

” When art is finally worthless, it will be free for everyone to make and enjoy.” – Destroying art in order to save human creativity

Creative Tyranny – Rob Horning

[I tend to think of Ben Davis as a useful idiot and this critique of his work spells out some of the reasons for that.]

Artists’ self-important claims for their work makes them worse than useless for political activism

Can you call yourself an artist and an activist at the same time? Or is the artists’ personal brand always in the way? 9.5 Theses on Art and Class, Ben Davis’s new collection of essays, addresses these questions and other similar ones with an admirable clarity that invites debate. In these pieces, Davis, a Marxist art critic and executive editor of Artinfo.com, shows little overt interest in policing the boundaries of art—there are virtually no assessments of the aesthetic value of particular artworks. Yet he ends up preserving a nebulous view of “great” art’s supposedly objective appeal that undermines his apparent political concerns. Art accrues meaning via its audience, which is inevitably structured by social relations. To imagine that its value can come from anywhere else is to obfuscate the centrality of class that Davis is otherwise eager to bring to light.

…

This makes artists inescapably individualistic, concerned chiefly about differentiating their product. As Davis notes, “an overemphasis on the creation of individual, signature forms—a professional requirement—can as often make it a distraction from the needs of an actual movement, which are after all collective, welding together tastes of all kinds.” Artists must produce their reputation as a singular commodity on the market, which makes their chief obstacle other would-be artists rather than capitalism as a system, regardless of whatever critical content might inhere in their work. When artists patronize the working class with declarations of solidarity, their vows are motivated less by a desire for social change than by the imperative that they enhance the distinctive value of their personal brand.

…

According to Davis, the artists’ class interest “involves defining creativity as professional self-expression, which therefore restricts it to creative experts”—the artists. Contemporary visual art, then, is a “a specific creative discipline that arrogates to itself the status of representing ‘creativity’ in general.” Rather than being a common property developed by the “general intellect” of workers in collaboration and social interaction, creativity becomes the intellectual property of certified artists alone, who, for their livelihood, administer it for the rest of society. That is, “real” creativity becomes the preserve of a specially trained elite rather than the evolutionary inheritance of the entire human species.

Whether or not it correlates to distinctions in talent, this distinction between the fake creativity of ordinary people working in common and the certified creativity of appointed artists working alone or atop a hierarchy allows those artists to make “artworks” with a value on the market. The point is to give only artists a true property stake in their creative activity—only their creative work has inherent value. Everyone else’s creative effort is just plain old “labor,” which is worthless until purchased by capital. Limiting authentic creativity to proven professional artists makes creativity both aspirational (it models how nonartists should structure their leisure) and vicariously accessible (nonartists can absorb creativity through awed exposure to properly certified art objects). It is thus that artists “represent creativity tailored to capitalist specifications.” Artists become the designated exemplars of the form liberty can take under an economic system that prizes innovation and glorifies ideologically the dignity of the small proprietor. Though Davis recognizes this, he also tries to give it a dialectical spin, arguing that the artists’ model of freedom demonstrates what autonomy looks like and why it might be worth struggling for.

…

…The structure of the entire art milieu is meant to forestall the broader appreciation of art and protect its capability to signify status. It is meant to allow rich people to recognize the fruits of their wealth in their exclusive access to the world’s finest things. The glory of the view lies primarily in its being private-access. Ordinary people’s appreciation of art attaches to works like so many barnacles, ruining their meaning for collectors. As with any luxury brand, the wrong sort of audience for an artist can sully their market value completely.

This is why so much of the discourse that surrounds contemporary art is so nauseating. It deliberately aims to destroy the confidence of nonelite audiences in their own judgment; it wants to make their potential pleasure in art depend on a recognition of their exclusion from the realm of art-making. We get the joy of knowing there’s some consumption experience beyond us that can remain forever aspirational, which gives us cause to cherish whatever brief peeks we get over the wall.

…

The same could be said of the world of literary journals, creative writing, and the “intellectual milieu” in general; each serves as a catch basin for those eager to transcend the ordinary economic relations that largely determine the lives of ordinary people. Often fueled by inherited privilege and a nurtured sense of entitlement, the up-and-coming cadres of the “creative class” seek ways to transform their yearning to be extraordinary into a career, and if that fails, into a politics based mainly on the demand for lucrative self-expression. All the while they imagine themselves exemplars of unsullied, disinterested aesthetic aspiration.

…

But it’s impossible to say artworks are “great” without also implying that those who can see that objective greatness are in a superior aesthetic position to those preoccupied with consumer junk. In wanting to preserve the traditional transcendental quality of art, Davis is arguing for the very same rarefied aura that critics and collectors and museums and art schools and all the other art-world institutions have always counted on and used as an alibi.

Far from working arm-in-arm with workers to liberate them from the forces that restrict their expression, artists are more likely to work to protect that aura and intensify the qualms ordinary people might have about thinking of their activities as art. Creativity must be held apart from consumerism, protected in the hands of a particular elite with the appropriate training to keep expression “authentically meaningful” rather than commercial. At the same time, authentic art production must be left in the hands of the professionals, who have been endowed with unique talent and have made a series of special sacrifices to develop their artistic gift. Ordinary people are endowed only with the ability to consume, and while they may think that’s creative, they’re kidding themselves.

…But that justification hinges on the idea that culturally recognized opportunities to be creative are scarce. It’s not that too many people are labeled artists then expected to work for less, as Davis suggests, but that not enough people recognize the artistry in what they are already doing and live with a sense of social inferiority and self-doubt. If they are to protect their own cultural capital, professional artists (and curators and critics) must endorse the standards that pronounce some people as uncreative.

…

Who cares about the sanctity of the “official culture,” which has a class-based interest in restricting that endorsement to a select few? The opportunities it provides and the self-realization that might stem from them are already poisoned from a political point of view. Davis won’t surrender the idea that “official approval matters” and that there is an objective basis for determining “legitimate self-expression.” Such official approval may matter to professional artists, because it is the source of their livelihood, and Davis seems eager to defend the right of a select few to make a living through art. To the rest of us, it is the stifling source of delegitimization. It is a reminder of the concrete reality of that solipsistic, insidery “art world” that Davis is otherwise so eager to see dismantled. Shouldn’t those excluded from the official art world create their own opportunities, according to their own communal standards, pitting their values against those of the official culture, and the social order that supports it, if necessary? Shouldn’t they destroy art to save it?

…

Similarly, in a postscript to his essay “White Walls, Glass Ceilings,” Davis urges we fight for “a world where art’s value escapes the deformities imposed upon it by an unequal society.” Davis wants there to be generalized social practices that can certify art’s value without somehow stratifying a society in which art has economic value. Yet if artistic ability is unequally distributed by nature, that fact alone will generate an unequal society as long as art is singled out for special cultural significance. Art is so complicit in structuring cultural hierarchies, it makes more sense to argue that art’s value never precedes the existence of those deformities and to agitate for a world where art is granted no alienable “value” at all.

In the collection’s last paragraph, Davis comes around to something like this position, that from the perspective of a future communist society, the idea that “great art was something rare and precious, a triumph that had to be scratched out against all odds, a privilege that needed to be defended with boundless righteousness and walled off in its own specific professional sphere will likely seem strange.” There is no reason to regard it as less than strange now. We can start by rejecting the need to identify “great” art and the class victors it nominates. When art is finally worthless, it will be free for everyone to make and enjoy.

to the degree that art embraces its status as a “profession” is the degree to which it acquiesces to instrumental rationality – Even more stuff I said on facebook with the really challenging, thoughtful, responses removed

When does a favor become “labor?” And as I’ve asked a thousand times before, who is *not* a “cultural producer?” That is, isn’t *everyone* making culture all the time? Therefore, why should the state subsidize only artist/curator errr…cultural producers that “count,” and not everyone else? Because the immeasurable impact/enrichment argument applies equally well to backyard gardeners and attentive parents doesn’t it?

…

You mentioned not helping friends…exploitation is a social relationship…something *experienced* not merely witnessed, or observed by an “expert.”

…

So, to you an internship is no “favor,” but to someone else it just might be.

…

And it sounds to me like your reserving some “specialness” for artists which is very convenient, but doesn’t stand up to scrutiny in my opinion

…

You ever see parents at a playground? Or see gardening clubs, email lists etc?

…

Ok. Drop the word internship. Use favor. If I’m preparing a meal for a big party and I need an “intern” to help me set the table, make drinks etc. I will hire a server. Get where I’m going?

…

Of course it is a fabrication, one that artists (self-interestedly) often accept. There is historical privilege that comes with being an artist and now that it is being diminished they are getting agitated. Not unlike men, whites, etc.

…

“I just don’t understand why certain people deserve compensation and others don’t for whatever kind of work is deemed important” – this is EXACTLY *my* question right? Why should artists be subsidized and not gardeners? Why should Gallery 400 get a grant and not a parent run play group?

…

If a friend of mine asks me to take care of their kid for the day, should I reject it unless I get paid?

…

You see, if art is merely a business relationship, not an endeavor among friends, then that is an “art” I have little time for. It might as well be data entry no? Because it seem to me artists often want it both ways – to be compensated based on some market model (wages, benefits), but not be obligated to perform under such a model….

…

I do hope you see how weird this is – like the most capitalist mind of all, every human sphere is to be monetized under your model. The only expression of gratitude is $$$. The only reward for a favor…errr….labor is $$$.

…

So, unpaid internships are undermining your wages and you (along with many others) are proposing a strike or boycott which is understandable, but live by the market, die by the market. What if, no one cares? I mean I haven’t been making art for like 20 years, haven’t been curating, haven’t been writing (in the “professional” sense). It has been a “protest” of a certain kind – and one that brings you face to face with a certain determination of “value.” If I’ve learned anything it is how useless the entire enterprise is – but it is liberating. Because having given up the notion that what I was doing was special allowed me to see the value in what everyone else is doing – the fly fishers,the role players, the whittlers, the bird watchers, the pick up basketball players, the fantasy football commissioners, etc. But maybe that was a lesson unique to me and my own hang ups…

But you haven’t done anything to clear up my confusion! I still don’t get why art folks want the govt. to support their hobby and not hot rod builders? Everyone for themselves?

…

Oh and art is no “personal choice?” You sound like a true liberal (as opposed to a communitarian) with your public/private compartmentalization. Smoking is also a choice but has deep social consequences. I would argue having children and raising them poorly has far deeper social consequences than making a shitty painting.

…

Furthermore, what is “provocative” for me is to see a group of folks who have lost their historical privilege griping about getting it back rather than wanting a more egalitarian distribution of “prestige” and or resources. The breakdown of high and low is celebrated in some corners of the art world until it translates into *actual* effects then the wagons get circled….

…

Parenting was only one example of “cultural production.”

…

It isn’t the zygote, it is the cascade of social effects.

…

And to the degree that art embraces its status as a “profession” is the degree to which it acquiesces to instrumental rationality.

…

And yeah I like my culture like my politics to be broad and inclusive….

…

You keep focusing on *one* example of mine. And it is not children that are culture/cultural production, but *parenting.* And “affective labor” is another silly term – Pardon me while I “work” at crying during this rom-com. And man I’m getting all upset by your comments, who will pay me for this uncompensated emotional “labor?”

I do appreciate you providing a normative definition of art, one that falls neatly into the subject of my forthcoming book. Privileging “critique” while certainly fashionable in the late 20th and 21st centuries reeks of grad school syllabus syndrome. It is dogma, but that doesn’t make it definitive.

But back to the notion of art as a “profession.” Why then if it is such, should it alone be exempt from the market?

Also, what is the benefit of your narrow definition of culture? Who benefits from the exclusion of non-“professionals” of so-called “cultural production” other than alleged experts?

…

Re: professional cultural producers

Let’s do the same with politics. We’ll leave everything in the hands of professional politicians. Let those who are properly trained tend to that stuff and let all the plebes do what they do best – acquiesce to those in the know.

“too little time spent on word and theory” – Art history as mere profession vs. contemplative practice – Let us stop building bibliographic tombs and instead cultivate an affinity for present experience

[Reading through my notes today on Practicing Mortality: Art, Philosophy and Contemplative Seeing. I discovered that one of the authors Joanna E. Ziegler died five years after its publication (at age 60). I read through various tributes and obituaries and this quote exemplifies the scope of her ambition, “The point is not just to teach them to design buildings, but to design their lives.” Her influence was clearly deep, if not broad and although I never knew her personally and her death was three years ago, the news still hurt – so passionate and beautiful was her life/pedagogical/spiritual/art/philosophical practice. If you can’t find time for the book I mentioned, the following essay concerning the Mission Statement of the College of the Holy Cross provides a glimpse of her holistic approach to the art of living.]

Wonders to Behold and Skillful Seeing: Art History and the Mission Statement – Joanna E. Ziegler

…

For me, that experience epitomized the nature of what this essay is about — ‘Living the Mission’ — especially as it continues to reshape my pedagogy and my professional identity. I wish the story I am about to unfold were seamless and easy, and that the wonderful insights gained at Collegium had been brought home to Holy Cross, yielding the bounty and sustaining the fervor they promised. The reality, however, is that for all my enthusiasm and commitment to ‘live the Mission,’ it remains, three years later, hard and sometimes confusing work. Confidence and optimism mingle with doubt, as the project of linking art to contemporary issues of living spiritually is alternately embraced and marginalized by the academic community.

…

‘Living the Mission’ affects professional practices and identity, as well, beyond the College’s gates and in the field of disciplinary inquiry. Art history is currently defined as a project to locate history — to locate subjectivity in the past — in quantifiable evidence and hard data, whose footings lie deep in sociology. Thus, any sort of personal, contemporary experience of historical form — the very thrust of my courses regarding art and contemplation — is looked upon skeptically, even censoriously as something better left to personal rather than professional journals. (2)

Part of this story, then, is about the taxing demands of persevering in a relationship of art conjoined to spirituality as a serious academic pursuit — that is, as a matter of genuine and significant intellectual content such as befits an academic discipline. For now, art history (as serious ‘scientific’ study) and spirituality (as religious non-academic experience — as a matter of faith) compete for ultimate authority in their absolutely separate domains. My attempt to ‘live the Mission’ is, in a very real sense, an effort to bridge that separation.

…

Conceived as something akin to a skill, the art of looking (or spectatorship) can occasion contemplation and mindfulness — inner states that are recognized nearly universally as the true paths toward spiritual awareness. Eastern meditation practices, Zen Buddhism, Benedictine spirituality, Western mysticism, Emersonian pragmatism, and stress reduction exercises, to name but a few, all seek to attain ‘wisdom’ through attention and awareness. Concentration is the cornerstone. As I envision it, then, the study of art — outside the studio — might appropriately take its place alongside other contemplative practices. It shapes contemplative consciousness by insisting on routine physical discipline, which enables readiness, and, in so doing, shows students the spiritual and intellectual depth of artistic creativity — for them as beholders, no less than for the creators.

Faith and creativity share a paradox, as I see it: fidelity and stability, gained through practice, prepare the way to true freedom. Only with readiness can one hope to transcend the constraints of practice (therein lies the paradox) and enter that place which is so mysterious, so immeasurable. The experience is so unlike the routine activity that gave rise to it, that all the names given that experience through time — transcendence, divinity, creativity, performance, ecstasy — cannot begin to capture its true nature.

…

Perhaps more disconcerting than its supposed similarity with Formalism, is the emphasis I place on the training or practice involved in looking. I emphasize the word training, for what happens in my classroom — and by extension the museum — seems understood as being more in line with studio or fine art, rather than art history per se. Colleagues who paint, sing, or dance embrace the sort of training I offer. Yet for art historians, it can smack of art appreciation and, worse, appear to offer insufficient servings of quantifiable, documentable, ‘hard’ evidence — the currently favored material for serious intellectual content. Too much emphasis on sensory and practical information, too much prominence of the present, and too little time spent on word and theory, is how my approach is seen as differing from current standards in teaching art history.

The joining of faith and spirituality with art — an important element in my approach — is a legitimate and long-standing aspect of art history, to be sure, but only when firmly lodged in period styles, such as Gothic or Renaissance. Professional groups have priorities and, at the moment, for works of art to have religious or spiritual significance, they must be of explicitly religious subject matter or have clearly devotional applications. In this view, the emphasis I place on developing a personal, present-day relationship with a work of art belongs, somehow, in the realm of New Age therapy rather than hewing to the ‘exacting’ professional standards of contemporary art history, which tend to see and contain works of art firmly within the time frame of their production.For me, therefore, the message of the Mission poses a dilemma. It asks me to heed its call, when to do so I must step beyond the boundary — to put it bluntly, to write myself out of the norms of publishable scholarship — of the very discipline that brought me to the College in the first place. True, the Mission Statement has inspired and enriched my thinking on creativity immeasurably, but I have had to leave the collegial setting of my discipline to pursue that thinking and to nurture thought into action.

On sabbatical this year, for example, I reflected long upon the contemplative lessons of great art and on the future of putting down scholarly roots among those lessons. I read a broad range of contemplative literature, which led, in part, to this essay and others like it. Meanwhile, my colleagues in art history were off to the archives and conferences in Europe, or reading vast amounts of post-Structuralist and deconstructionist theory. It may seem to them, therefore, that in my current activities I am abandoning the rigors of on-site research and voluminous bibliography-hunting for an apparently more relaxed, home-based form of intellectual pursuit. Such is by no means the case; reflection and contemplation are time-honored pillars of academic inquiry and pursuit. Nor do I want for challenges.

Where are the signposts of the Mission, so visible in campus conversation, as I thrash my way in isolation through the underbrush of this dilemma? The Mission Statement is a demanding document, more so than might appear on the surface. It presents a test of commitment to a purpose that diverges from the one that led me to Fenwick Hall some years ago. When I took my place among the other faculty of my Department, I vowed to be a loyal member of the field by bringing the best and most recent of its scholarly developments to our students. The evolution of the Mission Statement threw this vow into question, asking in a very tangible sense that I reassess and perhaps reorient my understanding of what I do and how that relates to the Mission. This I have done — but now, where am I ‘current’ as an art historian? What is my bibliographic base? Who, really, are my peers? And to what field do I or will I belong? ‘Living the Mission’ has been, in a word, costly.

Oh art “workers,” affective and cognitive “laborers,” and cultural “producers,” it would be great if you did some reading “work” on this article.

Manifesto against Labour – Krisis-Group

…

Usually the accused is given the benefit of doubt, but here the burden of proof is shifted. Should the ostracised not want to live on air and Christian charity for their further lives, they have to accept whatsoever dirty and slave work, or any other absurd “occupational therapy” cooked up by job creation schemes, just to demonstrate their unconditional readiness for labour. Whether such job has rhyme or reason, not to mention any meaning, or is simply the realisation of pure absurdity, does not matter at all. The main point is that the jobless are kept moving to remind them incessantly of the one and only law governing their existence on earth.

In the old days people worked to earn money. Nowadays the government spares no expenses to simulate the labour-”paradise” lost for some hundred thousand people by launching bizarre “job training schemes” or setting up “training companies” in order to make them fit for “regular” jobs they will never get. Ever newer and sillier steps are taken to keep up the appearance that the idle running social treadmills can be kept in full swing to the end of time. The more absurd the social constraint of “labour” becomes, the more brutally it is hammered into the peoples’ head that they cannot even get a piece of bread for free.

…

The new fanaticism for labour with which this society reacts to the death of its idol is the logical continuation and final stage of a long history. Since the days of the Reformation, all the powers of Western modernisation have preached the sacredness of work. Over the last 150 years, all social theories and political schools were possessed by the idea of labour. Socialists and conservatives, democrats and fascists fought each other to the death, but despite all deadly hatred, they always paid homage to the labour idol together. “Push the idler aside”, is a line from the German lyrics of the international working (labouring) class anthem; “labour makes free” it resounds eerily from the inscription above the gate in Auschwitz. The pluralist post-war democracies all the more swore by the everlasting dictatorship of labour. Even the constitution of the ultra-catholic state of Bavaria lectures its citizens in the Lutheran tradition: “Labour is the source of a people’s prosperity and is subject to the special protective custody of the state”. At the end of the 20th century, all ideological differences have vanished into thin air. What remains is the common ground of a merciless dogma: Labour is the natural destiny of human beings.

Today the reality of the labour society itself denies that dogma. The disciples of the labour religion have always preached that a human being, according to its supposed nature, is an “animal laborans” (working creature/animal). Such an “animal” actually only assumes the quality of being a human by subjecting matter to his will and in realising himself in his products, as once did Prometheus. The modern production process has always made a mockery of this myth of a world conqueror and a demigod, but might have had a real substratum in the era of inventor capitalists like Siemens or Edison and their skilled workforce. Meanwhile, however, such airs and graces became completely absurd.

Whoever asks about the content, meaning, and goal of his or her job, will go crazy or becomes a disruptive element in the social machinery designed to function as an end-in-itself. “Homo faber”, once full of conceit as to his craft and trade, a type of human who took seriously what he did in a parochial way, has become as old-fashioned as a mechanical typewriter. The treadmill has to run at all cost, and “that’s all there is to it”. Advertising departments and armies of entertainers, company psychologists, image advisors and drug dealers are responsible for creating meaning. Where there is continual babble about motivation and creativity, there is not a trace left of either of them – save self-deception. This is why talents such as autosuggestion, self-projection and competence simulation rank among the most important virtues of managers and skilled workers, media stars and accountants, teachers and parking lot guards.

The crisis of the labour society has completely ridiculed the claim that labour is an eternal necessity imposed on humanity by nature. For centuries it was preached that homage has to be paid to the labour idol just for the simple reason that needs can not be satisfied without humans sweating blood: To satisfy needs, that is the whole point of the human labour camp existence. If that were true, a critique of labour would be as rational as a critique of gravity. So how can a true “law of nature” enter into a state of crisis or even disappear? The floor leaders of the society’s labour camp factions, from neo-liberal gluttons for caviar to labour unionist beer bellies, find themselves running out of arguments to prove the pseudo-nature of labour. Or how can they explain that three-quarters of humanity are sinking in misery and poverty only because the labour system no longer needs their labour?

It is not the curse of the Old Testament “In the sweat of your face you shall eat your bread” that is to burden the ostracised any longer, but a new and inexorable condemnation: “You shall not eat because your sweat is superfluous and unmarketable”. That is supposed to be a law of nature? This condemnation is nothing but an irrational social principle, which assumes the appearance of a natural compulsion because it has destroyed or subjugated any other form of social relations over the past centuries and has declared itself to be absolute. It is the “natural law” of a society that regards itself as very “rational”, but in truth only follows the instrumental rationality of its labour idol for whose “factual inevitabilities” (Sachzwänge) it is ready to sacrifice the last remnant of its humanity.…

Labour is in no way identical with humans transforming nature (matter) and interacting with each other. As long as mankind exist, they will build houses, produce clothing, food and many other things. They will raise children, write books, discuss, cultivate gardens, and make music and much more. This is banal and self-evident. However, the raising of human activity as such, the pure “expenditure of labour power”, to an abstract principle governing social relations without regard to its content and independent of the needs and will of the participants, is not self-evident.

In ancient agrarian societies, there were all sorts of domination and personal dependencies, but not a dictatorship of the abstraction labour. Activities in the transformation of nature and in social relations were in no way self-determined, but were hardly subject to an abstract “expenditure of labour power”. Rather, they were embedded in complex rules of religious prescriptions and in social and cultural traditions with mutual obligations. Every activity had its own time and scene; simply there was no abstract general form of activity.

It fell to the modern commodity producing system as an end-in-itself with its ceaseless transformation of human energy into money to bring about a separated sphere of so-called labour “alienated” from all other social relations and abstracted from all content. It is a sphere demanding of its inmates unconditional surrender, life-to-rule, dependent robotic activity severed from any other social context, and obedience to an abstract “economic” instrumental rationality beyond human needs. In this sphere detached from life, time ceases to be lived and experienced time; rather time becomes a mere raw material to be exploited optimally: “time is money”. Any second of life is charged to a time account, every trip to the loo is an offence, and every gossip is a crime against the production goal that has made itself independent. Where labour is going on, only abstract energy may be spent. Life takes place elsewhere – or nowhere, because labour beats the time round the clock. Even children are drilled to obey Newtonian time to become “effective” members of the workforce in their future life. Leave of absence is granted merely to restore an individual’s “labour power”. When having a meal, celebrating or making love, the second hand is ticking at the back of one’s mind.

…

The political left has always eagerly venerated labour. It has stylised labour to be the true nature of a human being and mystified it into the supposed counter-principle of capital. Not labour was regarded as a scandal, but its exploitation by capital. As a result, the programme of all “working class parties” was always the “liberation of labour” and not “liberation from labour”. Yet the social opposition of capital and labour is only the opposition of different (albeit unequally powerful) interests within the capitalist end-in-itself. Class struggle was the form of battling out opposite interests on the common social ground and reference system of the commodity-producing system. It was germane to the inner dynamics of capital accumulation. Whether the struggle was for higher wages, civil rights, better working conditions or more jobs, the all-embracing social treadmill with its irrational principles was always its implied presupposition.

…

…No ruling caste in history has led such a wretched life as a “bondman” as the harassed managers of Microsoft, Daimler-Chrysler or Sony. Any medieval baron would have deeply despised these people. While he was devoted to leisure and squandered wealth orgiastically, the elite of the labour society does not allow itself any pause. Outside the treadmills, they don’t know anything else but to become childish. Leisure, delight in cognition, realisation and discovery, as well as sensual pleasures, are as foreign to them as to their human “resource”. They are only the slaves of the labour idol, mere functional executives of the irrational social end-in-itself.

…

Thus “labour”, according to its root, is not a synonym for self-determined human activity, but refers to an unfortunate social fate. It is the activity of those who have lost their freedom. The imposition of labour on all members of society is nothing but the generalisation of a life in bondage; and the modern worship of labour is merely the quasi-religious transfiguration of the actual social conditions.

…

The workers’ movement itself became the pacemaker of the capitalist labour society, enforcing the last stages of reification within the labour system’s development process and prevailing against the narrow-minded bourgeois officials of the 19th and early 20th century. It was a process quite similar to what had happened only 100 years before when the bourgeoisie stepped into the shoes of absolutism. This was only possible because the workers’ parties and trade unions, due to their deification of labour, relied on the state machinery and its institutions of repressive labour management in an affirmative way. That’s why it never occurred to them to abolish the state-run administration of human material and simultaneously the state itself. Instead of that, they were eager to seize the systemic power by means of what they called “the march through the institutions” (in Germany). Thereby, like the bourgeoisie had done earlier, the workers’ movement adopted the bureaucratic tradition of labour management and storekeeping of human resources, once conjured up by absolutism.

…

After centuries of domestication, the modern human being can not even imagine a life without labour. As a social imperative, labour not only dominates the sphere of the economy in the narrow sense, but also pervades social existence as a whole, creeping into everyday life and deep under the skin of everybody. “Free time”, a prison term in its literal meaning, is spent to consume commodities in order to increase (future) sales.

…

On the contrary, our contemporaries quite generally only ascribe meaning, validity and social significance to an activity if they can square it with the indifference of the world of commodities. His labour’s subjects don’t know what to make of a feeling like grief; the transformation of grief into grieving-work, however, makes the emotional alien element a known quantity one is able to gossip about with people of one’s own kind. This way dreaming turns into dreaming-work, to concern oneself with a beloved one turns into relationship-work, and care for children into child raising work past caring. Whenever the modern human being insists on the seriousness of his activities, he pays homage to the idol by using the word “work” (labour).

The imperialism of labour then is reflected not only in colloquial language. We are not only accustomed to using the term “work/labour” inflationary, but also mix up two essentially different meanings of the word. “Labour” no longer, as it would be correct, stands for the capitalist form of activity carried out in the end-in-itself treadmills, but became a synonym for any goal-directed human effort in general, thereby covering up its historical tracks.

This lack of conceptual clarity paves the way for the widespread “common-sense” critique of labour society, which argues just the wrong way around by affirming the imperialism of labour in a positivist way. As if labour would not control life through and through, the labour society is accused of conceptualising “labour” too narrowly by only validating marketable gainful employment as “true” labour in disregard of morally decent do-it-yourself work or unpaid self-help (housework, neighbourly help, etc.). An upgrading and broadening of the concept labour shall eliminate the one-sided fixation along with the hierarchy involved.

Such thinking is not at all aimed at emancipation from the prevailing compulsions, but is only semantic patchwork. The apparent crisis of the labour society shall be resolved by manipulation of social awareness in elevating services, which are extrinsic to the capitalist sphere of production and deemed to be inferior so far, to the nobility of “true” labour. Yet the inferiority of these services is not merely the result of a certain ideological view, but inherent in the very fabric of the commodity-producing system and cannot be abolished by means of a nice moral re-definition.

…

This way the attempt to use opposing interests inherent in the system as a leverage for social emancipation is irreversibly exhausted. The traditional left has finally reached a dead end. A rebirth of radical critique of capitalism depends on the categorical break with labour. Only if the new aim of social emancipation is set beyond labour and its derivatives (value, commodity, money, state, law as a social form, nation, democracy, etc.), a high level of solidarity becomes possible for society as a whole. Resistance against the logic of lobbyism and individualisation then could point beyond the present social formation, but only if the prevailing categories are referred to in a non-positivist way.

…

You will argue that superseding private property and abolishing the social constraint of earning money will result in inactivity and that laziness will spread. So you confess that your entire “natural” system is based on nothing but coercive force? Is this the reason why you dread laziness as a mortal sin committed against the spirit of the labour idol? Frankly, the opponents of labour are not against laziness. We will give priority to the restoration of a culture of leisure, which was once the hallmark of any society but was exterminated to enforce restless production divested of any sense and meaning. That’s why the opponents of labour will lose no time in shutting down all those branches of production which only exist to let keep running the maniac end-in-itself machinery of the commodity producing system, regardless of the consequences.

…

According to this spirit, the opponents of labour want to create new forms of social movement and want to occupy bridgeheads for a reproduction of life beyond labour. It is now a question of combining a counter-social practice with the offensive refusal of labour.

May the ruling powers call us fools because we risk the break with their irrational compulsory system! We have nothing to lose but the prospect of a catastrophe that humanity is currently heading for with the executives of the prevailing order at the helm. We can win a world beyond labour.

Workers of all countries, call it a day!

“the human being is above all a creature of repetition and artistry” – Keith Ansell-Pearson on Peter Sloterdijk

Philosophy of the Acrobat: On Peter Sloterdijk – Keith Ansell-Pearson

…

The thesis that religion has returned after the alleged failure of the Enlightenment project needs to be confronted, Sloterdijk argues, with a clearer view of what we can legitimately consider as “spiritual facts.” Such a consideration shows that the return to and of religion is impossible since, so goes Sloterdijk’s initial contention, religion does not, in fact, exist. Instead, what exist are only misunderstood spiritual regimens. All human life requires the cultivation of matters of body and soul, and all philosophies and religions have attended to this fundamental feature of our existence. By this view, any clear-cut dichotomy of believers and unbelievers falls away. In place of this dichotomy, we should distinguish between the practicing and the untrained, or those who train differently.

…

…He wishes to give a new truth to the insight developed by Marx and the Young Hegelians in the 1840s that contends that “man produces man”: in short, the human being is never given to itself or to anything else, but produces and reproduces its own conditions of existence and as a project of personal development, even an adventure. Sloterdijk, however, differs from Marx and the Hegelians in not wanting to place the stress on labor or work as the key category by which to understand this self-forming process of man. He proposes that the language of work be transfigured into that of “self-forming and self-enhancing behaviour.” We need, then, to go beyond both the myth of homo faber and of homo religiosus and to understand the human being as a creature that results from repetition. As he notes, humans live in habits, not in territories. If the 19th century can be viewed as standing under the sign of production, and the 20th century under the sign of reflexivity, then we need to grasp the future under the sign of the exercise. None of this refining and purifying work is without significance for our understanding of the human animal, since it holds the potential for unlocking anew the secrets of the human animal, including a reinvigoration of the key words by which we understand our so-called spiritual life, words such as “piety,” “morality,” “ethics,” and “asceticism.”

…

…For Sloterdijk the human being is above all a creature of repetition and artistry, the “human in training” as he puts it, or which we could call shaping and self-shaping. Not only is the earth the ascetic planet par excellence, as Nietzsche contended, it’s also the acrobatic planet par excellence.

Sloterdijk contends that human beings are always subject to “vertical tensions” in all periods and in all cultural areas: “Wherever one encounters human beings, they are embedded in achievement fields and status classes.” I take Sloterdijk to be referring in general terms to the self-surpassing tendencies of the human animal, or its perfectionist aspirations. Thus, he recalls at the outset the Platonic Socrates, saying that man is the being who is potentially superior to himself. He takes this to indicate that all cultures and subcultures rely on distinctions by which the field of human possibilities gets subdivided into polarized classes: religious cultures are founded on the distinction between the sacred and the profane; aristocratic cultures base themselves on the distinction between the noble and the common; military cultures establish a distinction between the heroic and the cowardly; athletic cultures have the distinction between excellence and mediocrity; cognitive cultures rely on and cultivate a distinction between knowledge and ignorance; and so on. There is thus in humans an upward-tending trait, and this means for Sloterdijk that when one encounters humans, one will always find acrobats. One great modern “myth” of our time that captures this, and the idea of verticality in general, is that of Nietzsche’s tale in Thus Spoke Zarathustra of the being that is fastened on a rope between animal and superhuman. What model of vertical perfection and “progress” is encapsulated in this idea?

This is where matters get controversial in Sloterdijk’s study since he is dealing with matters such as training in the sense of “breeding” that have a highly dubious history. However, here he endeavors to be dexterous in his appreciation of projects that aim to fashion new human beings. On the one hand, he takes seriously Nietzsche’s seemingly fantastical ideas about the ?bermensch; on the other, he is severely critical of the “Soviet” attempt to create a new human and a new society by means of large-scale social and technological engineering. In reading Nietzsche, Sloterdijk does not find a biological or eugenics program (in spite of all the talk about “breeding” in Nietzsche), but an artistic and acrobatic discourse in which the emphasis is on training, discipline, education, and self-design. As Nietzsche has Zarathustra say, one builds over and beyond oneself — but to do this well one needs to be built first “four-square in body and soul.” The human subject needs to be seen as a carrier of “exercises,” made up of, on the passive side, an aggregate of individuated effects of habitus, and, on the active side, a center of competencies that allow for some minimal sense of self-direction and self-mastery. Should we thus not calmly agree with Nietzsche that egotism is but “merely the despicable pseudonym of the best human possibilities”?

…

Why art critics need to be DTF – Or why it is fine if reading e-flux is more like Ok! Magazine or facebook and less like The Book of Mormon

Get Off – Nick Faust

[I think there are plenty of artists that are guilty of the same things he accuses critics of, but he has the spirit right.]

…

Art criticism, like an upset parent, often passes moral judgment on this promiscuity, scolding, judging indiscretions. There are attempts at keeping art pure, delineating what is what, and who is who, and where the boundaries are. Or in the attempt to redefine the boundaries, there is a tendency to violently sabotage what came before if it doesn’t smoothly fit into the new regime.

But it’s crucial to encourage brief brushes, longed-for encounters, and magical moments that pass into the night to be brokenly remembered in the hungover daze of the next morning. Flings, one night stands, and vacation hook-ups are just as ripe. For artists who tie the knot—explosive divorces, whimpered muttering and weepy withdrawals, quiet bitter unspoken tension.

Likewise, art writing must attempt to draw new connections, weaving in unpublished, hushed talk that always gets spoken but generally not on the record. The documentation of the piece, the Facebook posts, tweets, and vines that surround such work, the gossip about the work in the bathrooms of the gallery and outside during the smoke breaks and back in the patios and bars after the opening, the press releases both in unchecked email and listserv format, and the 10,000 art-opening invites that networked artists receive each day on social media, the write-up of the work, the studio visits, the sketching out of the ideas, the conversations that influence and sustain the practices—all these are rich and evocative and can provide tremendous energy and meaning to a work and extend its life out beyond.

…

I think of people getting made up and fabulous, ready for a night on the town, scoffing at such prudes who advise a more “natural” and “authentic” way of representing themselves—their elaborate play and fluidity as they cycle from situation to situation, conversation to conversation, adjusting on the fly and letting themselves take in the experience while also manipulating it.

…

Instead, the proliferation of work on the Internet makes it easily digestible and citable. New practices, in Sanchez’s view, instantly devour themselves. I think it is necessary to flip the destructive, gluttonous connotations of devouring and focus on the more positive connotations of the word, that emphasis on avid enjoyment. What is so appealing about such fast distribution is how the institutionalized approaches that once suffocated, purified, cleansed, and straightened up the circulation of art are now infused with the chitchat and gossip of social life, and the work is tossed out onto the dance floor, knocked down from the balcony overlooking the frenzy. It isn’t, “Oh my, check out that stoic hottie—that removed, super-distant installation at Kunsthalle Wien. Man, I wish I could ask him if he wants to dance, but I’m so nervous, and he’s so up there.” Instead, in both the quick-feed call and response and riffing and sharing, it is shooting a flirty raise of the eyebrow, adjusting your posture accordingly, and striking up a conversation and making the advance. The stilting and privileging, the attempts to put one group up above another, are falling apart. Everybody is fucking everybody.

…

Artists don’t have to sign a mortgage with the things they work with, and it is perfectly normal to kind of hate the people you’re attracted to. Gosh, she’s so wonderful and smart and well-read and funny, but she’s a horrible drunk and she farts in her sleep. Or: he’s such a belittling and abusive asshole, but I kind of need that deprecation in my life right now, it is hot, I can’t help myself, I know it isn’t “normal” but it is working so well right now. Please keep the stories coming, and the encounters memorable.

…

Music hasn’t traditionally been as reliant on proximity to or participation in certifying institutions in the way visual art has. A producer from the middle of nowhere can throw up a track on Soundcloud after being inspired by some other, more-well-connected artist and quickly enter into the dialogue.

Visual art should be jealous of this fluid accessibility, these leveling maneuvers. Kids far from the art capitals can give themselves a playful legibility that is constantly up to be teased out and undermined. It isn’t realistic for young would-be gallerists to acquire a space like the De Vleeshal, but with a little paint and lighting know-how, they can transform their crappy garage, bombed-out basement, or parent’s attic into their own gallery space that is gonna look great all done up and out there.

…

Why privilege one level of the art speech act over another? Sure, some work might be underwhelming in person, in comparison to the space that looked so big onscreen, but the work is just as true in the studio as it is in the gallery, as it is on a website, as it is in a book, as it is on a phone, as it is during pedicure and manicure parties, as it is when barely remembered and floating as an example to be used in a conversation that never quite makes it out, as it is in a minuscule press clipping that some art historian will dig up a hundred years from now while writing a dissertation. Each new iteration allows for an unlimited amount of possibilities for artists to use, to extend and pause and speed up and burrow in and rewind and cut and paste and reverse and queer and undo and build upon, and as such, none should be shut down.…

“Leftists favor full employment…I favor full unemployment.” – Requiem for labor (day)

The Abolition of Work – Bob Black

[A true classic on this Labor Day. This essay shows why David Graeber’s recently circulated essay “Bullshit Jobs” makes so little sense to me. Jobs are bullshit -ipso facto.]

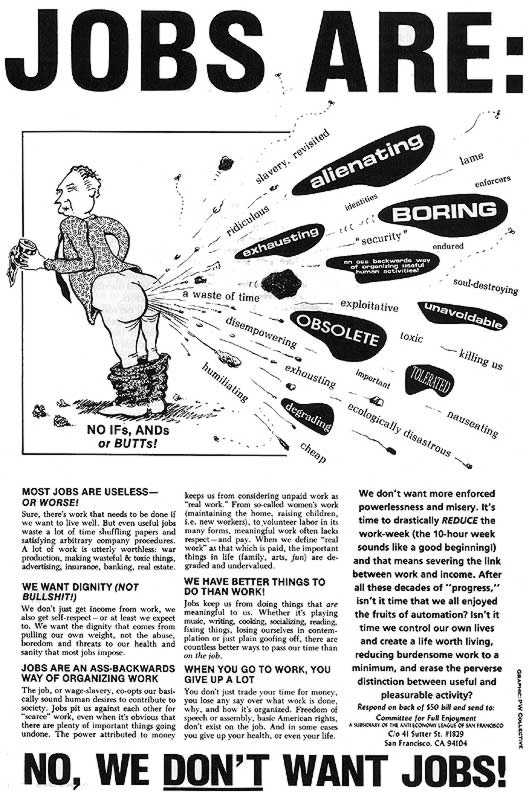

No one should ever work.

Work is the source of nearly all the misery in the world. Almost any evil you’d care to name comes from working or from living in a world designed for work. In order to stop suffering, we have to stop working.

That doesn’t mean we have to stop doing things. It does mean creating a new way of life based on play; in other words, a ludic revolution. By “play” I mean also festivity, creativity, conviviality, commensality, and maybe even art. There is more to play than child’s play, as worthy as that is. I call for a collective adventure in generalized joy and freely interdependent exuberance. Play isn’t passive. Doubtless we all need a lot more time for sheer sloth and slack than we ever enjoy now, regardless of income or occupation, but once recovered from employment-induced exhaustion nearly all of us want to act.

The ludic life is totally incompatible with existing reality. So much the worse for “reality,” the gravity hole that sucks the vitality from the little in life that still distinguishes it from mere survival. Curiously — or maybe not — all the old ideologies are conservative because they believe in work. Some of them, like Marxism and most brands of anarchism, believe in work all the more fiercely because they believe in so little else.